CAP Theorem explained with a horse and carriage

You are king or queen of a vast realm. Your subjects depend on your wise decision making, and your law to maintain order.

Therefore you've written down all laws so that every citizen knows what is lawfully permitted, and what is a criminal offense.

It would hardly be just if somebody was punished for a crime they did not know existed. You decide it's important for all people to be able to see these laws. You send your messengers across the kingdom to the many cities in your realm, each with a tablet inscribing all of the laws, to be placed in the public square and announced for those who can't read.

Unfortunately, some of your messengers return with reports that a major road has been blocked by a flood. The river is uncrossable. There is simply no way to deliver the tablets until the flood waters recede, which coud be weeks.

This puts you in a conundrum. You could hold off on adopting these new laws on principle that everybody must see the same sets of laws. But it could be some time.

The Yellow River Breaches Its Course by Ma Yuan, 1160-1225

The CAP theorem can be used to explain this situation. It was originally envisioned as a pick any two:

- Consistency (Every city has the same laws)

- Availability (There are laws on display, even if they are out of date)

- Partition Tolerance (Roads being blocked)

The more modern thinking on the CAP theorem is that partitions are unavoidable. Just like a King or Queen can't stop a flood, network engineers can't always stop a broken router or a server from going dark.

Consistency suggests that all computers in the network have the same data, just like all cities in our kingdom see the same sets of laws. Due to blocked roads, you're forced to hide the laws from everybody until you can be sure that every city has seen the new set of laws.

If you relaxed that requirement, you allow some cities to show maybe an older version of the laws even when the roads are blocked, you're choosing to prioritize availability. Prioritizing availability means that for some cities, the laws may be out of date, but at least there's some laws on display, potentially important to keep the peace. While the flood is ongoing, cities outside of the reach of the Capital operate on their own set of laws.

The only way to stay consistent (to have all laws be the same) and available (the laws are on display) is to have clear roads and no partitions. To make sure everybody is on the same page, you'd want riders returning from each city confirming that the new laws are in fact on display, at which point you can confidently say the laws are universal.

Databases make these tradeoffs when replicating or horizontally scaling. Postgres recommends many ways of replicating your data. Some of them are consistent:

Shared Disk Failover

Uses a single disk array that is shared by multiple servers. If the main database server fails, the standby server is able to mount and start the database as though it were recovering from a database crash. This allows rapid failover with no data loss.

One significant limitation of this method is that if the shared disk array fails or becomes corrupt, the primary and standby servers are both nonfunctional

File System (Block Device) Replication

All changes to a file system are mirrored to a file system residing on another computer. The only restriction is that the mirroring must be done in a way that ensures the standby server has a consistent copy of the file system

SQL-Based Replication Middleware

A program intercepts every SQL query and sends it to one or all servers. Each server operates independently. Read-write queries must be sent to all servers, so that every server receives any changes. But read-only queries can be sent to just one server, allowing the read workload to be distributed among them.

Care must also be taken that all transactions either commit or abort on all servers, perhaps using two-phase commit (PREPARE TRANSACTION and COMMIT PREPARED).

Notice how all of these methods require the replica to be online. That's the price of consistency. Other Postgres replications relax the consistency, and focus more on availability:

Write-Ahead Log Shipping

Warm and hot standby servers can be kept current by reading a stream of write-ahead log (WAL) records. If the main server fails, the standby contains almost all of the data of the main server, and can be quickly made the new primary database server.

Logical Replication

Logical replication allows a database server to send a stream of data modifications to another server.

On the other hand, if there are other writes done either by an application or by other subscribers to the same set of tables, conflicts can arise.

Trigger-Based Primary-Standby Replication

Operating on a per-table basis, the primary server sends data changes (typically) asynchronously to the standby servers.

Because it updates the standby server asynchronously (in batches), there is possible data loss during fail over.

Asynchronous Multimaster Replication

Each server works independently, and periodically communicates with the other servers to identify conflicting transactions. The conflicts can be resolved by users or conflict resolution rules.

Notice how all of these availability first strategies all involve some form of data loss (not consistent) when a failover happens and if writes are allowed on replicas there are conflicts that need to be resolved. That's the price of availability.

Once the roads clear, your messengers deliver the laws to the furthest parts of your kingdom. You can rest assured knowing that nobody will be punished for a law they were unaware of. That is, until you need to make changes to the law. You're getting nervous about any blocked roads as you're starting to realize it's the same problem all over again.

Calculating Pi in 5 lines of code

Known as the Madhava–Leibniz method of calculating Pi. Originally known as the Leibniz formula for calculating Pi, it was discovered that Indian mathmematician and astronomer Madhava of Sangamagrama (or perhaps his followers) had formalized this method of calculating Pi in the 14th-15th century. A naming improvement since Leibniz already has too many formulas named after him.

It's beautifully simple. 1 - 1/3 + 1/5 - 1/7 + 1/9... continued to infinity gets you 1/4th of Pi.

And it's very easy to write in code. Here it is using python:

quarterPi = 0

for i in range(0, 1000000):

numerator = 1 if i % 2 == 0 else -1

denominator = i * 2 + 1

quarterPi += numerator / denominator

print(quarterPi * 4)

If we run this code, we get 3.1415916535897743, which is surprisingly close to Pi, accurate to the 6th decimal.

Infinite series can't really be calculated to completion using a computer, but that for i in range(0, 1000000): line controls how many iterations you calculate for (currently 1 million).

If we crank it up to 100 million iterations we can really make our CPUs work:

3.1415926525880504

100 million iterations took 180 seconds on my computer, and it's now accurate to the 8th decimal. Now, what about if we only loop 100 times?

3.1315929035585537

Not very accurate. It took my computer less than half of a millisecond to compute 100 iterations.

It's incredible to think that mathematicians were able to come up with this formula in a time when they couldn't necessarily check the results by hand.

User /u/Another_moose came up with this one line version of the algorithm:

sum(-(i*8%16-4)/(i*2+1) for i in range(10**6))

Mathematics can really illustrate how powerful programming can be, often with very little effort. Code representing math often ends up being some of the most concise, maybe because these two fields of study share some deep parallels.

Networking explained with a horse and carriage

Imagine you're a king or queen ruling over a vast realm.

Key to your power is knowledge. You've maintained a network of horse riders and stables for your messengers to use as they bring news from far parts of the kingdom to you.

One day, you have an incredible proclamation, a wedding invitation for the grandest ceremony and party.

UDP

You pay several local villagers to ride their horse to a city in the realm, each carrying a "save the date" letter. Since the date is far off you tell the messengers that their job is done after delivering the message.

This would be analogous to sending UDP packets. Messages are sent without confirmation of delivery. After giving these instructions to the riders you realize you don't know when or if the letters arrived at their destination.

After sending the letters you get some unfortunate news. One of the most important guests cannot attend that date, and so the wedding date will have to be changed. You repeat the process, sending out messengers with the new date.

Some of the letters with the new date arrive sooner than the letters with the old dates. You end up getting confused envoys asking which date is the real date. This is known in computer networking as Out-of-order_delivery.

Determined not to create any more chaos you hire the wisest thinkers to implement a system that can deliver messages in order reliabily. Here is a system they came up with. They call it TCP.

TCP

You use a trusted courier that will deliver the message, then return with confirmation that the message has been delivered. Easy enough. Your thinkers also tell you to write down a number on each message corresponding to the number of letters sent to that destination. That way the recipient knows if a message comes out of order.

TCP is like this trusted courier. TCP is a protocol that provides reliable, ordered delivery of data.

Once the courier returns, they get sent out again, this time to acknowledge (ACK packet) that the confirmation was received by the original sender. Although it's a lot of travel, missing messages can be noticed when the acknowledgement has gaps in the numbering.

Some computer terminology: The time it takes for the messenger to travel from the capital to its destination is called Latency. Instead of messengers you would call them "packets". Ping would be how long it takes for a full round-trip. In this analogy some of the messages may be time-sensitive (especially as the wedding date gets closer). If a message doesn't arrive to its destination for any reason (bandits? treacherous cliffsides?), it might not be noticed until the next message is received, and then it would still require a messenger to be sent back to the capitol in order to request a copy of the missing of letters. This increased number of round-trips and additional latency is one of the big reasons TCP is not a great system for fast communication (like in fast paced games).

In real life before trains, latency would measure in days, weeks, or even months for very far off destinations. But in computer networks, latency is anywhere between a few milliseconds to... well, actually there is no upper limit.

Light could theoretically circumnavigate the Earth within 133 milliseconds, which means our best fiber optic cables could feasibly see latency as low as 66ms for somebody on the other side of the world. This number is optimistic because there's always slow down from hops along different routers to and along the internet backbone, and from wifi or satellite. There can also be lots of internet "traffic" which bottlenecks some routes around the internet causing lag spikes.

When you navigate to a website or play an online game, you can imagine signals traveling back and forth between your computer and the server that hosts that website or game. Every time you see the page load or the contents update, some data must have been exchanged. Imagine if a message is lost because a line went dead or one of the many routers on the route had a bug or reset. In UDP those messages would be lost forever. With TCP, there is a way for the sender and receiver to request the missing messages but with a big latency penalty equal to the round trip time. The basic principles of message passing still are followed in the same way they were when the word was spread by horse and carriage. Many complex networking related topics like the Cap Theorem can be explained by the horse and carriage analogy – because at its core it boils down to simple message passing.

Custom made wood lapdesk

I use my laptop often and deal with neck strain, so I thought I'd build myself a lapdesk capable of raising my laptop closer to eye level.

The design is pretty simple. A stand and base connected by a basic doorhinge, and some legs that can lock into slots along the base.

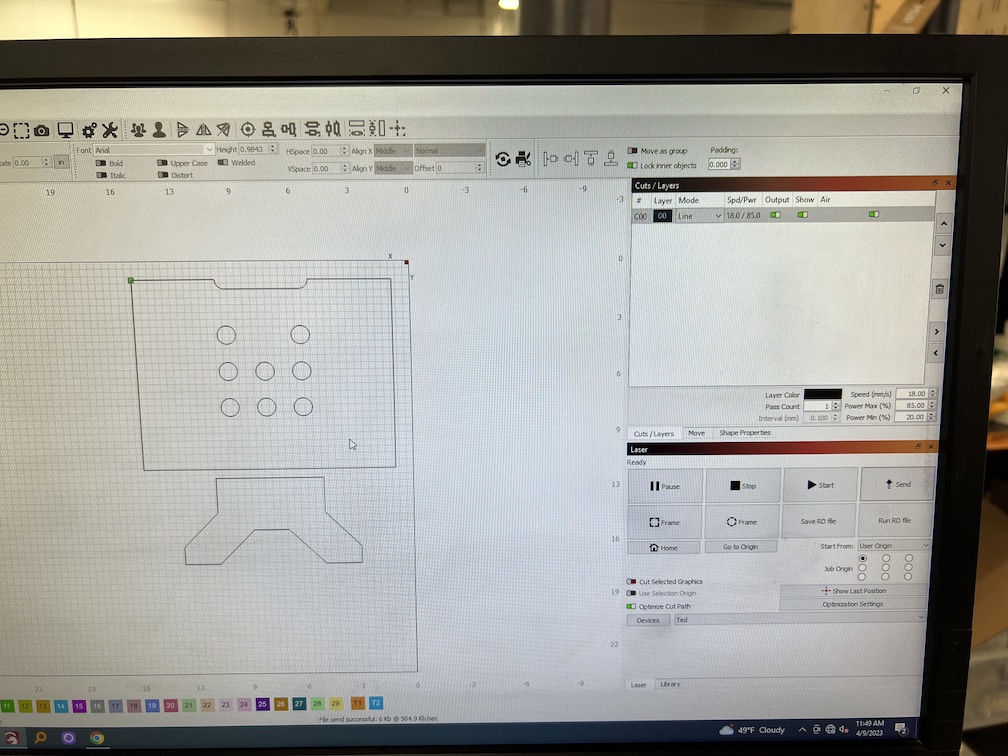

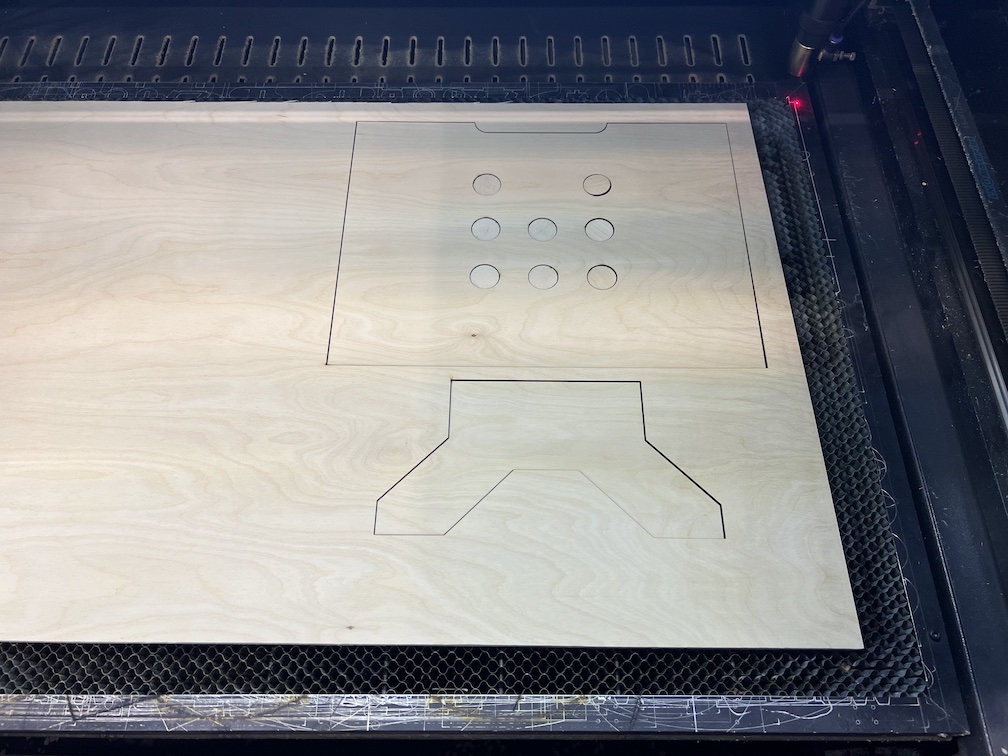

I had originally tried using a CNC router to cut out the piece but found it took too long to cut. This time I used a laser cutting machine.

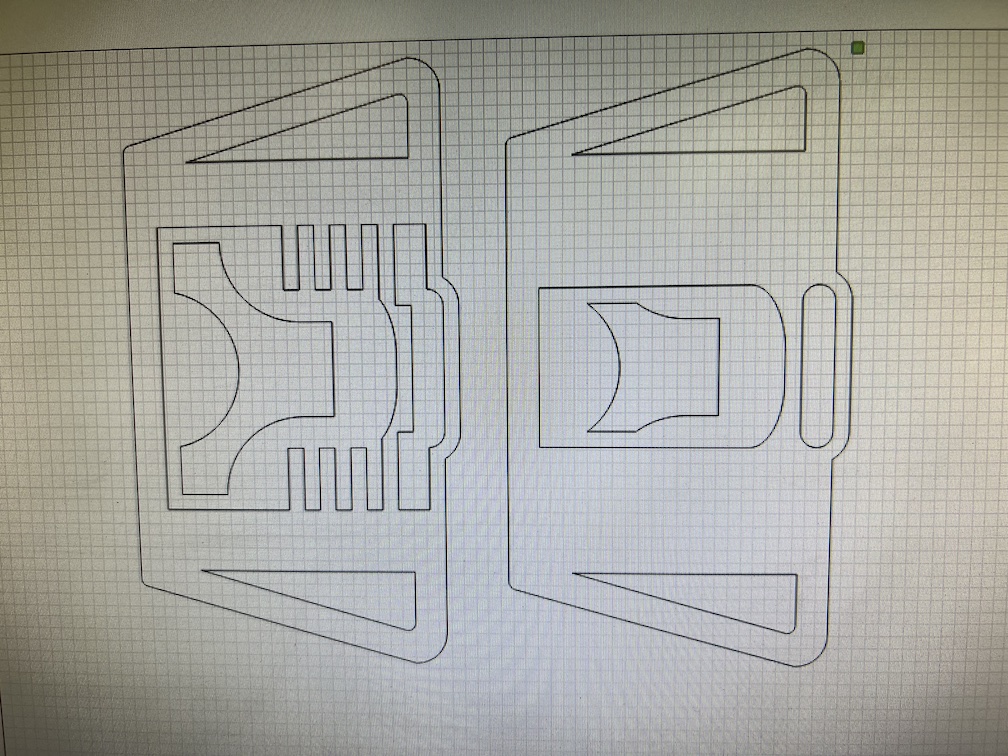

Using the lightburn software, I mocked up the designs. Lightburn is somewhat cumbersome, I would recommend using a different software like illustrator and export to SVG.

This is the laser cutter. Shout to Seattle Makers.

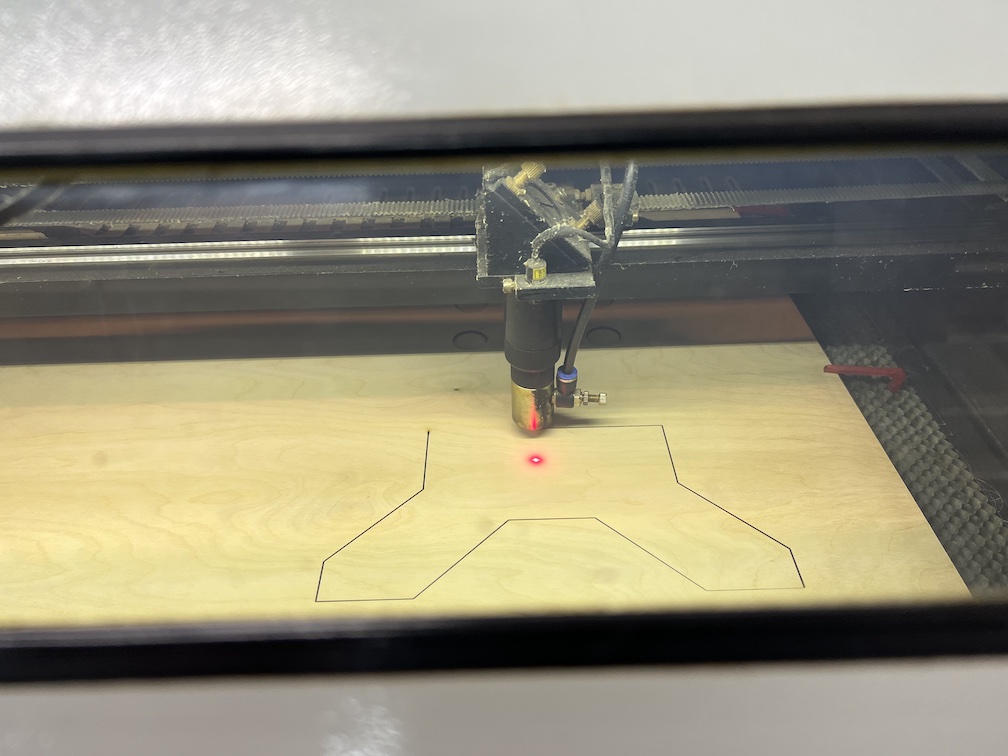

The cut was pretty quick, less than a half hour. It's also quite precise. The edges are burnt uniformly, giving it a pretty unique appearance. The plywood also smells nice and woody while lasering.

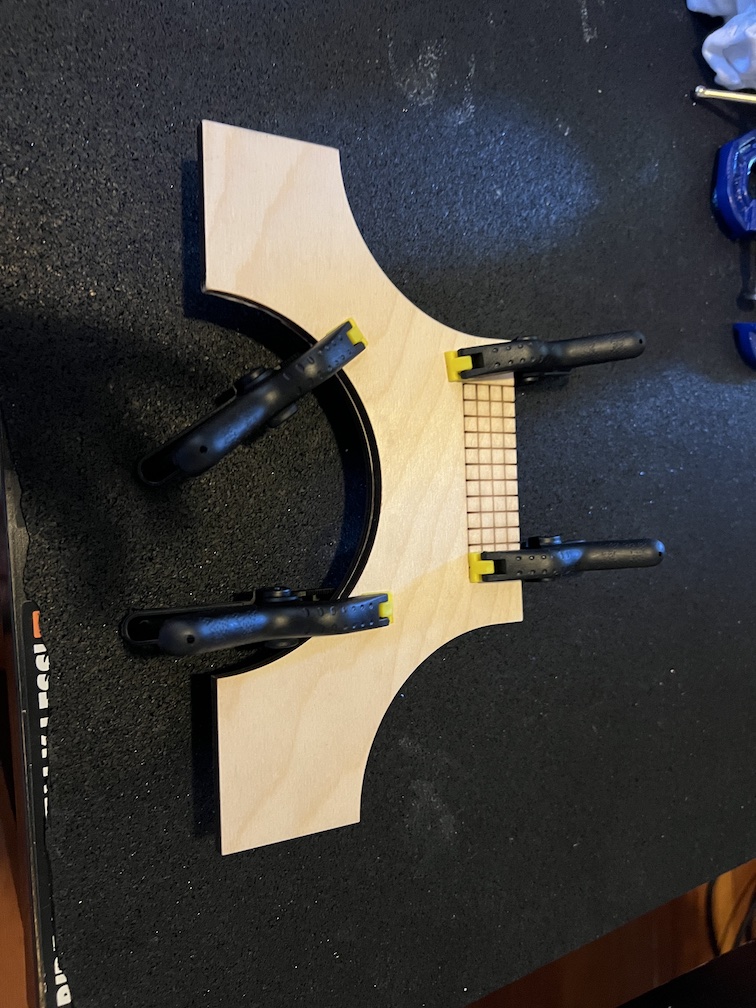

Once cut, I glued pieces together, essential to have gaps for the legs to slot into.

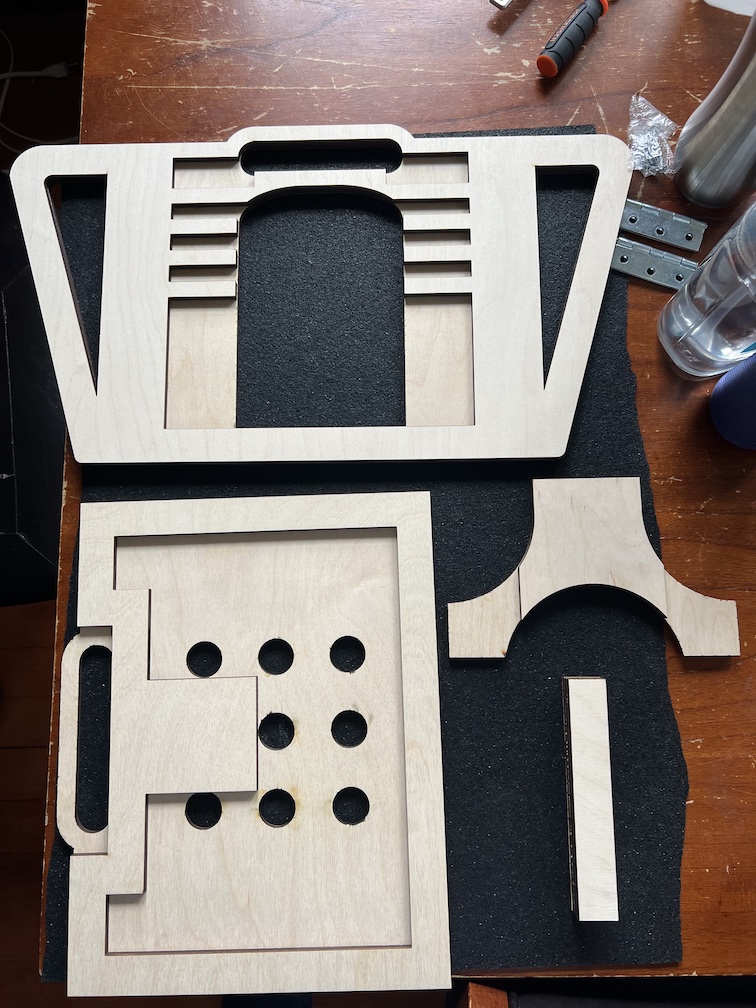

You can see the design taking shape. I sourced regular old door hinges and assembled the final product.

Here's a side profile of an earlier design (the CNC routed attempt).

The completed product

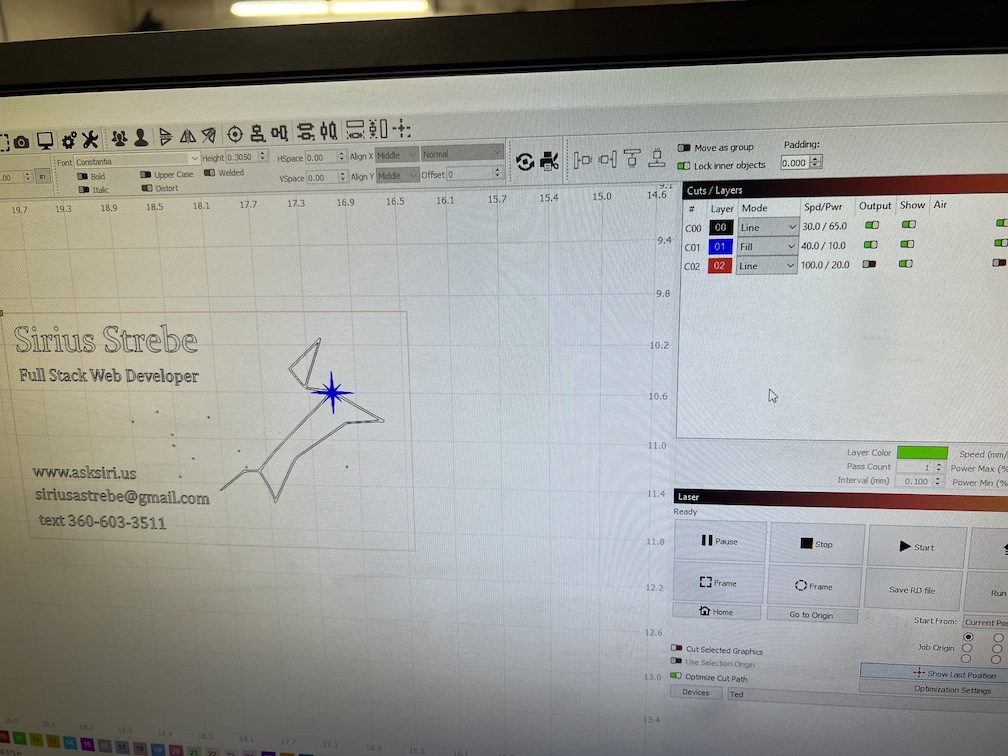

Ask Sirius business cards!

I made this using a laser cutter, lightburn software, and an anodized aluminum card.

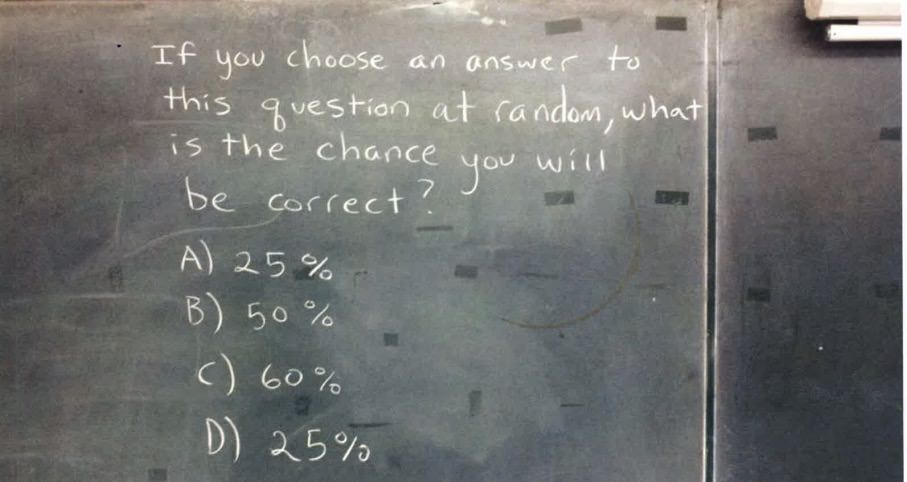

When statistics asks about itself

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 25%

(b) 50%

(c) 50%

(d) 100%

What do you think the answer is?

And just as crucially why do you think the other answers are NOT correct? Take your time, this one is a head scratcher.

---

---

---

---

---

Ready for the answer?

---

---

---

Well, they all seem kind of correct!

(a) 25% can be argued as correct because there's a 1 in 4 chance of landing on (a).

Both (b) and (c) look correct at 50%, since they together account for half of the options.

And finally if all of the options we've seen have been correct, then wouldn't (d) 100% also be true?

In this scenario, we have a circumstance where there are no wrong answers. How can this be?

Reflect for a moment whether you disagree or agree.

This problem is so fascinating because it's self-referential. The answer affects the question. It's asking about itself. A cool property of self-referential questions like this that unlike normal questions, the options available changes the answers to the question.

Let's change the question around a little bit to get an idea of how it works.

One correct answer

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 0%

(b) 25%

(c) 98%

(d) 100%

There's one obviously correct answer about. (b) 25%. One in four chance of landing on (b), and no other answer seems correct.

It might, at first glance look like (a) 0% could be a correct answer, but if it were correct wouldn't the probability of picking it be greater than 0%?

In this question, 0% is a funny answer, because it can never be right. It's like saying This statement is false. The question is asking what the probability is of being correct in choosing 0%. If the correct answer is 0%, you couldn't possibly be correct!

It's a contradiction, and can really be seen in this example:

Nonsensical answers

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 0%

(b) 0%

(c) 0%

(d) 0%

It can be hard to keep track of what the question is even saying. 0% probability implies we cannot possibly get the answer right. But since it's the only option, we're guaranteed to land on it 100% of the time.

0% is wrong in that you can land on it. That would then make it correct in saying 0% is the wrong answer. Does that make it right, wrong, or somehow both?

Reductio ad absurdum

Multiple correct answers

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 3%

(b) 50%

(c) 50%

(d) 99%

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 1%

(b) 75%

(c) 75%

(d) 75%

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 100%

(b) 100%

(c) 100%

(d) 100%

In the last example, all options are true! So convenient.

No correct answers

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 0%

(b) 25%

(c) 25%

(d) 100%

Sadly, none of these options make much sense. 25% appears twice, so you're 50% likely to land on a 25%, which sounds suspiciously like a contradiction.

Origin

I originally found a variant of this question on Imgur.

In this original question, it appears that there are no correct answers. Little appears to be known about the original author. The question is so interesting because it's such a rich and fascinating insight into mathematics, and how we grapple with probabilities.

Mathematical arguments

Both Bayesian and Frequentist statisticians would find fault with the question itself.

A frequentist could take samples of the question - but we don't actually know how to verify if an option chosen is actually correct!

Take our original example with 25%, 50%, 50%, 100% options. We would indeed land on 25% with 25% probability, 50% with 50% probability, but 100% with only 25% probability. So 100% could be argued as least correct of all of these.

I wrote a script to use Python 3's built in random library to sample the questions and compare the answers. Be warned, this code doesn't answer the question directly but instead its counterfactual: Assuming the option chosen is true, what is the chance of it being landed on? Here's a sample output of the script.

0.25 is within 1% correct: 0.250050

0.5 is within 1% correct: 0.498430

1 is incorrect: 0.251520

My good friend mgsloan argues,

'If (a) (b) (c) are all "consistent" and that is the same as "correct", then it could be argued that the correct answer should be 75%, and so no answer is correct.'

He brings up a convincing point that only deepens the mystery of this question. What if (d) were instead 75%? Would it be more true? Would that then make the true answer 100%, or would it still be 75%?

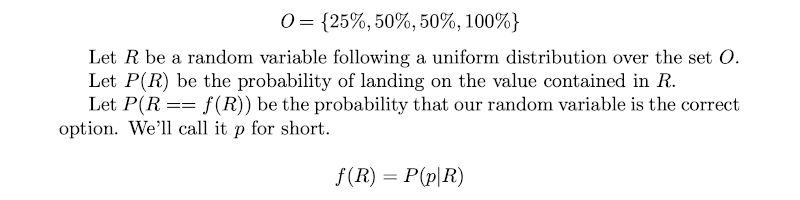

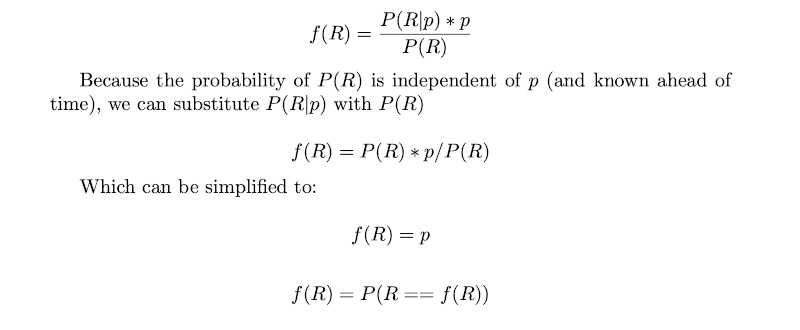

Bayesians fair no better, even though it almost sounds like a Bayesian question in the form Given I chose this option randomly, what's the chance it's correct? Formulating it into a mathematical equation we get:

The above statements are recursive, which makes sense given the problem. Bayes' Theorem states that we can rearrange the probability like such:

The last statement only confirms our suspicions that this problem is inherently self-referential, yet it yields no secrets about itself, besides how the question never was Bayesian to begin with.

If you were looser with mathematics, you might argue that you could take a random normal distributions and multiplied it by the options supplied. 25% + 50% + 50% + 100% = 225%, averaged would give us 56.25%, which makes no sense either, since we're adding together probabilities from options that could be incorrect and therefore shouldn't contribute to our total.

I've heard some argue the set of solutions is of cardinality 3, and it looks like {25%, 50%, 100%}, therefore the true answer is 1/3, 33.333...%. I have no comment whether or not this approach more or less accurate than thinking about 4 options.

Conclusion

How can such a simple question be so impenetrable to analysis?

In my opinion the reasons we come up with for our answers to questions like these is the fascinating part.

Kind of like time travel paradoxes, self reflective reasoning can lead to all sorts of strange contradictions like Godel's incompleteness theorem. These problems are the edges of reasoning because of their abstractness and yields not a correct answer, but in their self-reflective nature turns the mirror onto us and lays bare the rationalizations we construct to justify them.