When statistics asks about itself

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 25%

(b) 50%

(c) 50%

(d) 100%

What do you think the answer is?

And just as crucially why do you think the other answers are NOT correct? Take your time, this one is a head scratcher.

---

---

---

---

---

Ready for the answer?

---

---

---

Well, they all seem kind of correct!

(a) 25% can be argued as correct because there's a 1 in 4 chance of landing on (a).

Both (b) and (c) look correct at 50%, since they together account for half of the options.

And finally if all of the options we've seen have been correct, then wouldn't (d) 100% also be true?

In this scenario, we have a circumstance where there are no wrong answers. How can this be?

Reflect for a moment whether you disagree or agree.

This problem is so fascinating because it's self-referential. The answer affects the question. It's asking about itself. A cool property of self-referential questions like this that unlike normal questions, the options available changes the answers to the question.

Let's change the question around a little bit to get an idea of how it works.

One correct answer

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 0%

(b) 25%

(c) 98%

(d) 100%

There's one obviously correct answer about. (b) 25%. One in four chance of landing on (b), and no other answer seems correct.

It might, at first glance look like (a) 0% could be a correct answer, but if it were correct wouldn't the probability of picking it be greater than 0%?

In this question, 0% is a funny answer, because it can never be right. It's like saying This statement is false. The question is asking what the probability is of being correct in choosing 0%. If the correct answer is 0%, you couldn't possibly be correct!

It's a contradiction, and can really be seen in this example:

Nonsensical answers

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 0%

(b) 0%

(c) 0%

(d) 0%

It can be hard to keep track of what the question is even saying. 0% probability implies we cannot possibly get the answer right. But since it's the only option, we're guaranteed to land on it 100% of the time.

0% is wrong in that you can land on it. That would then make it correct in saying 0% is the wrong answer. Does that make it right, wrong, or somehow both?

Reductio ad absurdum

Multiple correct answers

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 3%

(b) 50%

(c) 50%

(d) 99%

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 1%

(b) 75%

(c) 75%

(d) 75%

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 100%

(b) 100%

(c) 100%

(d) 100%

In the last example, all options are true! So convenient.

No correct answers

If you chose an answer to this question at random,

what is the probability you will be correct?

(a) 0%

(b) 25%

(c) 25%

(d) 100%

Sadly, none of these options make much sense. 25% appears twice, so you're 50% likely to land on a 25%, which sounds suspiciously like a contradiction.

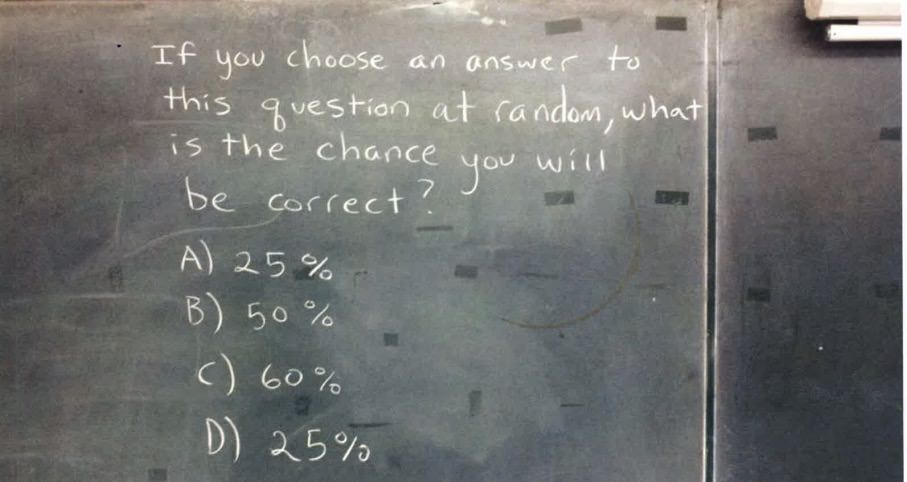

Origin

I originally found a variant of this question on Imgur.

In this original question, it appears that there are no correct answers. Little appears to be known about the original author. The question is so interesting because it's such a rich and fascinating insight into mathematics, and how we grapple with probabilities.

Mathematical arguments

Both Bayesian and Frequentist statisticians would find fault with the question itself.

A frequentist could take samples of the question - but we don't actually know how to verify if an option chosen is actually correct!

Take our original example with 25%, 50%, 50%, 100% options. We would indeed land on 25% with 25% probability, 50% with 50% probability, but 100% with only 25% probability. So 100% could be argued as least correct of all of these.

I wrote a script to use Python 3's built in random library to sample the questions and compare the answers. Be warned, this code doesn't answer the question directly but instead its counterfactual: Assuming the option chosen is true, what is the chance of it being landed on? Here's a sample output of the script.

0.25 is within 1% correct: 0.250050

0.5 is within 1% correct: 0.498430

1 is incorrect: 0.251520

My good friend mgsloan argues,

'If (a) (b) (c) are all "consistent" and that is the same as "correct", then it could be argued that the correct answer should be 75%, and so no answer is correct.'

He brings up a convincing point that only deepens the mystery of this question. What if (d) were instead 75%? Would it be more true? Would that then make the true answer 100%, or would it still be 75%?

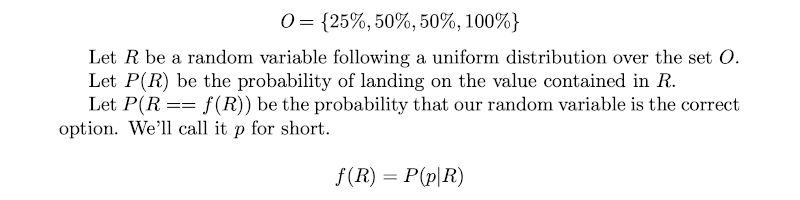

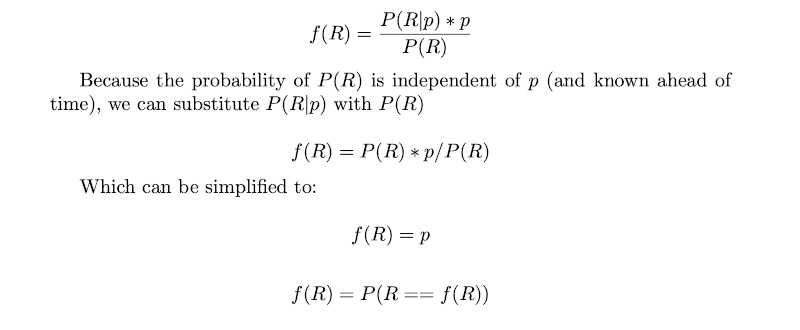

Bayesians fair no better, even though it almost sounds like a Bayesian question in the form Given I chose this option randomly, what's the chance it's correct? Formulating it into a mathematical equation we get:

The above statements are recursive, which makes sense given the problem. Bayes' Theorem states that we can rearrange the probability like such:

The last statement only confirms our suspicions that this problem is inherently self-referential, yet it yields no secrets about itself, besides how the question never was Bayesian to begin with.

If you were looser with mathematics, you might argue that you could take a random normal distributions and multiplied it by the options supplied. 25% + 50% + 50% + 100% = 225%, averaged would give us 56.25%, which makes no sense either, since we're adding together probabilities from options that could be incorrect and therefore shouldn't contribute to our total.

I've heard some argue the set of solutions is of cardinality 3, and it looks like {25%, 50%, 100%}, therefore the true answer is 1/3, 33.333...%. I have no comment whether or not this approach more or less accurate than thinking about 4 options.

Conclusion

How can such a simple question be so impenetrable to analysis?

In my opinion the reasons we come up with for our answers to questions like these is the fascinating part.

Kind of like time travel paradoxes, self reflective reasoning can lead to all sorts of strange contradictions like Godel's incompleteness theorem. These problems are the edges of reasoning because of their abstractness and yields not a correct answer, but in their self-reflective nature turns the mirror onto us and lays bare the rationalizations we construct to justify them.